Pew Research Center often conducts surveys around the globe on sensitive topics, including religion and national identity. Asking balanced questions about these kinds of topics is a challenging endeavor that requires us to invest considerable time and effort into developing and testing questionnaires.

But our recent survey of nearly 30,000 Indian adults required even more questionnaire development phases, over a longer period of time, than are typically undertaken at the Center. Through these efforts, we sought to produce a survey instrument that could be easily understood by respondents across India’s diverse regions and religious communities, while also asking about sensitive issues in an appropriate way.

The questionnaire development process took over two and a half years, concluding in the fall of 2019. Along the way, we consulted with subject-matter experts, conducted focus groups and qualitative interviews, and fielded both a survey pretest and a pilot survey. Between each phase of the development process, we refined the questionnaire. (Fieldwork for the main survey began in mid-November 2019. You can read more about the fieldwork in this Decoded post.)

The participants for our test studies came from a variety of backgrounds (taking into account their religion, gender, age, socio-economic status, languages spoken and location) to ensure that our questions were well-suited for a wide swath of the Indian public. An in-country institutional review board, or IRB, also approved the questionnaire — including the consent language — to protect the rights and privacy of the respondents.

Below is a description of our main efforts to develop and refine the survey questionnaire:

1. Background research (throughout the survey development process): In the earliest stages of the project, our main task was to identify the broad themes we wanted to cover in the survey that were both measurable through opinion data and relevant to India’s public discourse. We looked at previous surveys conducted in India and met with academics, journalists and policy experts to better understand where there may be data gaps that we could address. Throughout the project, we followed the news and looked for additional research on social issues in India that could improve the questionnaire.

2. Academic advisers (throughout the survey development process): We recruited a board of six academic scholars with diverse methodological and subject area expertise within the broad topic of religion and identity in India. They provided input on questionnaire topics and gave feedback on the wording of specific questions. Once fieldwork was completed, they also provided feedback on the analysis and editorial choices. While the project was guided by our consultations with these advisers, Pew Research Center alone determined which questions to include in the final questionnaire and how to analyze the results.

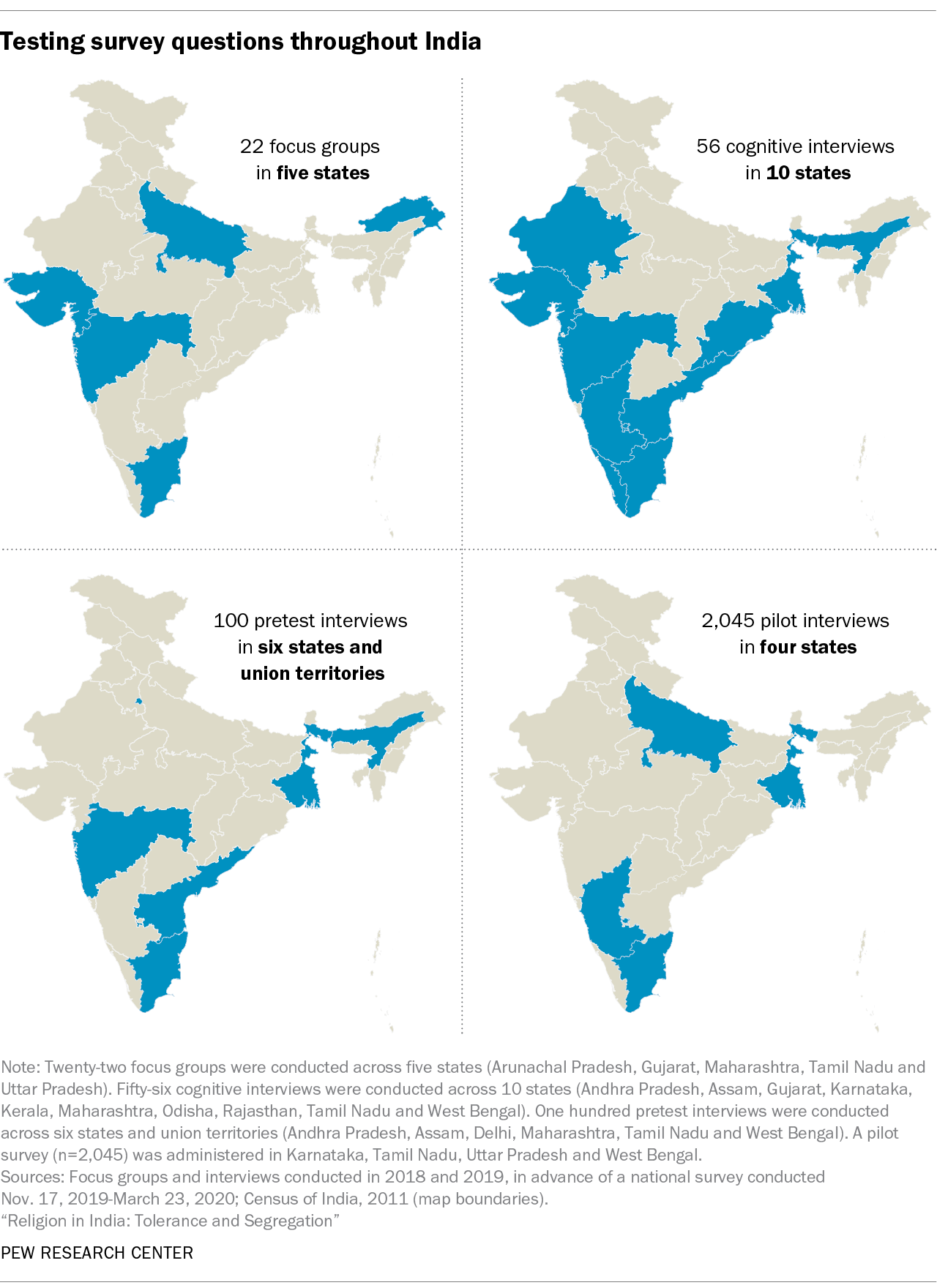

3. Focus groups (April-May 2018): We conducted 22 focus groups across five Indian states in four languages: Hindi, Tamil, Gujarati and Marathi. These moderated group discussions were an initial opportunity to understand how Indians talked about key issues and to see how comfortable participants were when having these discussions. Focus groups were organized around demographic characteristics; for example, urban Muslim women met to discuss religion, diversity, nationalism and gender. While the participants generally talked about our research topics with ease, in our assessment of qualitative interviews, religious conversion emerged as a topic too sensitive to phrase into a question. As a result, we did not include questions assessing attitudes toward proselytizing and conversion in the questionnaire, although we did measure the rate of religious switching. (For more information on religious conversion in India, see the report.)

4. Cognitive interviews (September-October 2018): We held 56 cognitive interviews across 10 Indian states, helping us better understand how respondents think through their response process. In these individual sessions, we asked participants to answer survey questions and then asked follow-up prompts to gauge participant discomfort and comprehension. We conducted these interviews in 10 languages: Assamese, Bengali, Gujarati, Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Odia, Tamil and Telugu.

One conclusion from the cognitive interviews was that Indians have widely varying understandings of the phrase “the West.” We asked participants, “Please tell me if you completely agree, mostly agree, mostly disagree or completely disagree with the following statement: There is a conflict between India’s traditional values and those of the West.” As a follow-up question, we asked, “Which countries are parts of the West?” While academic discussions often consider places like the United States or Western Europe as “the West,” the Indians in our cognitive interviews also listed countries like China, Japan, Pakistan and Saudi Arabia as parts of “the West.” We therefore decided to remove “the West” from the questionnaire to avoid any data inconsistencies that could be created by these varying interpretations.

In one instance, based on cognitive interviews, we significantly changed a question aimed at assessing attitudes on diversity. We originally asked, “Is it better for us that our country is composed of people from different languages and religions OR would it be better for us if our country were composed of people with the same language and religion?” Some respondents gave us feedback that the wording of the second option could be understood as inflammatory and that they were uncomfortable with the question. As a result, we decided to include a different version of this question in the final instrument: “All in all, do you think India’s religious diversity benefits the country or harms the country?”

Throughout our qualitative work, Indian respondents enthusiastically shared their opinions on the topics covered in the survey. At the end of one cognitive interview, for example, a female respondent volunteered that no one had ever talked to her in so much detail about her opinion on these issues, even though she had so much to share through her personal experiences. Indian respondents’ enthusiasm for the survey topic was also reflected in the response rate for the nationally representative survey: 86% of the people we contacted to participate in the survey ended up completing an interview.

5. Pretest (March 2019): After the questionnaire was fully translated into 16 local languages and the translations were independently reviewed by additional translators, it was tested with 100 Indians across six states and union territories. In this test, we conducted full interviews with participants and asked questions of the interviewers after each interview was over. We asked interviewers to evaluate the quality of the translations and how burdensome the questionnaire was for respondents.

During the pretest, we recorded the start and end times of each interview to get a better sense of interview length. The pretest revealed that the interviews were running quite long, on average, and risked respondent fatigue. We therefore made significant cuts to the questionnaire.

We also improved the flow of the questionnaire by reordering and simplifying the wording of some questions. For instance, instead of asking if the “Partition of 1947” was a good thing or bad thing for Hindu-Muslim relations — a phrasing that lacked clarity and required the respondent to know a specific date — we concentrated the question on the impact of the “partition of India and Pakistan” on Hindu-Muslim relations.

6. Regional pilot (July-September 2019): The pilot survey (n=2,045) in four states was our final chance to test all survey processes before national fieldwork began. Beyond questionnaire edits, this included checking interviewer training procedures and practicing data quality checks.

The regional pilot also gave us an opportunity to conduct question wording experiments by asking half the respondents one version of a question and the other half a modified version. The data from the two groups could then be compared to see if question wording made a difference to the results. For example, we conducted an experiment on how best to ask about perceptions of discrimination against members of Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs). We asked half of the pilot sample if there is a lot of discrimination against both SCs and STs, and the other half was asked separately about SCs, then STs. We found no noticeable difference between asking about discrimination against SCs and STs at the same time, as part of the same question, or asking about them separately. Therefore, we could decide which question version to use based on our editorial priorities. (For more about measuring caste in India, see this Decoded post.)

The large sample size of the pilot study also allowed us to look for potentially unexpected results that could point toward translation or cognition issues. In one instance, Sikhs were asked, “Do you generally keep your hair uncut?” A significant portion responded “no.” We knew this result was very unlikely, given that these respondents expressed high levels of religious observance on other measures. We found that the term “uncut” was creating a cognitive issue because of the negative phrasing. So we simplified the question wording to: “Do you generally keep your hair long?” This and other examples illustrate how repeated testing can be highly beneficial to improving the validity of survey questions.